Mary Lorenzo

February 24, 2006

MR. BARRY:

Well, tell us how you started

work at Sparrows Point. Did you grow up in this area?

MS. LORENZO:

No, I worked at Westinghouse.

MR. BARRY:

Where did you grow up?

MS. LORENZO:

I grew up in

Cockeysville

, and

I was married and had three children, I divorced, and I

went to work at Westinghouse in

Cockeysville

and

meanwhile then I remarried, and I got pregnant and I

thought well, “I have worked all my life, I'm going to

stay home.” Well, I just couldn't be a Suzie homemaker,

I just don't like that, you can tell, but I just didn't

like that. I liked physical work, and a friend of mine

had moved in these old apartments in

Essex

across

from Salvo’s, they are torn down, and one of my

neighbors, her husband worked at the shipyard, and she

said my husband said they are hiring at

Bethlehem

Steel, the steel mill, do you want to go down there,

and I said “yes.”

So we went down, it was in 1971, April of

1971, and I made less money at Bethlehem Steel on turn

work than I made at Westinghouse when I left there, but

that's how I got started, and I would get laid off and

stuff, but it didn't bother me at that time because I

was married.

And then when my second husband and I broke

up, you know I couldn't take these layoffs, so I

transferred over to the steel side, and it was me and a

lady Mary Denny, she is deceased now, and she had to go

back to work because she was single to get the benefits

for her children, and we went to the employment office,

they said the only place we have for you is the

batteries, and we are thinking “car batteries.” Well,

what can be bad with batteries? They are saying, "Oh,

they are terrible," and I can remember Mary and I, we

signed up, we went to work. So we go to the steel

side -- now, we had been on the finishing side all this

time and you know how the parking lots are.

Well, when we got to the steel side, we

parked and we start walking, we had to go to the coke

ovens, and we are walking and walking and we are saying

to everybody “how do you get to the coke ovens,” they

said “keep going down here.” We are walking, we said

they are giving us the runaround, they don't want women

here. We didn't realize how far you had to walk. I

mean you had to walk, and I guess it was around '73 --

no, I think '76. Anyway, around '78 or something

before they had a bus that would pick you up and take

you, but I mean it was a long walk.

And I went into the labor gang, I went on to

batteries, and it was the hardest work, they put me in

the mud mill.

MR. BARRY:

And what were the batteries?

MS. LORENZO:

The batteries were where they

made the coke, and it was like I guess coal comes -- I

don't know how they do it, but they would put it --

they had a machine on top that would go over and would

drop this coal I guess down into the holes, and that

would bake for so long, and then they had like one

machine on one side would be a pusher and it would line

up to the door, and at that time they had mud -- they

had men that did the mudding, and then on the other

side would be the catcher, and it would push that ram

rod right on through.

But I worked in the mud mill, and it was --

you would go out and you would clean these runs. When

they would push that coke out, you would have to go

with a wheelbarrow and a shovel and all and load it in

the wheelbarrow and take it back, and there was a big

round thing, a prehistoric big round, had a wheel that

went like this and water, and you threw this coke in

there and you went down below and you got clay, you put

clay in there, and it would mix it into a mud, and as

it came into the mud, then I think you opened it up

like a little trough, and it would shoot out on the

floor, and on seven and eight batteries -- they had up

to twelve. I worked five and six I think it was, but

anyway, seven and eight, people on five and six or

three and four would have to make the mud for seven and

eight. I don't know why they didn't have a mud mill,

but when I first went there the guy said here's your

job. Well, I stuck my shovel in that mud, Bill, and I

couldn't pull it out, the suction was holding it, and

at the end of the day I would have a pile about that

big on that shovel, because it killed you, but you made

mud.

You had to make so many batches of mud, and

then I think around two o'clock, that was the last time

you had to have your mud made, and that was the last --

the next shift -- it was clear for like two hours.

So with the guys, I was slowing them down. I

mean I was working, but I was slowing them down, so we

made a deal, I would go out and clean all the runs

because they made their last batch of mud I think like

at one o'clock, and I would go clean the runs and they

were finished at 1:00, and they knew that I would do

all that. And so finally I went to Johnny Fair, I went

in to get off because like I said my son at that time,

my oldest son was in Stembridge Football League, and I

wanted to go see the games, and on the batteries you

worked turn work, and I can remember going to Johnny

Fair and going up to -- I can't remember who the

superintendent was at the coke ovens, and he said “boy,

you just -- you have too much of an outside life.

Maybe you just better quit, you've got too much going

on outside.”

So there were guys that wanted to get on he

batteries because they made the money. The yard gang

just cleaned up the coke that fell on the ground and

stuff like that. So that's what happened. I had more

seniority than a lot of them so that's how when I

wanted to get off, I got out. That's what saved me

with Johnny. I have to say Johnny did fight for me,

maybe toward the end, you know, after everybody started

seeing it, the picture changes, and everything was

fine, I can't complain about anything. I mean other

than you know the flirting and the stuff like that, but

I mean I could handle that.

It was just when I went into the crafts, and

I mean it wasn't me, Paula Bouche was in there before

me in refrigeration, and I mean it was awful, awful,

and the guys -- there were some guys that were really

good friends of mine and they seen what was being done

to me, but it was just like that movie [

North Country

]

going to stick up, and the only person who stuck up for

me was Dave Fenwick, and the foreman had the police

come over and took his locker out and swore that his

locker hadn't been in there, you know, retaliated

against him and all, and Dave transferred out -- this

was in the late '90s I guess or 2000. Dave transferred

out and went into -- I don't know if it was the bull

gang or the pipe itters or something.

MR. BARRY:

Go back and tell us what happened

when you went -- why did you go into the crafts, and

when was this?

MS. LORENZO:

I can't remember.

MR. BARRY:

Roughly.

MS. LORENZO:

I'm saying '79 was when I went

into the crafts. There was positions opened for

electrical helpers over at ERS and refrigeration, and I

had gone and taken -- gone over and taken the

electrical helper's test and all and passed it, and

when I went over to the employment office, it was a

gentleman at that time named Mr. Holland, and he was

really nice, and I was telling him, you know, why I

wanted this job, and he says, "Well, Mary, the best job

is the refrigeration." He said, "But the only trouble

is you've got the worst boss in the world." He said

that was Larry Reece, and I thought well, I can go over

there, and when I went over there, I didn't really --

Larry was one of these ones that really hollered at

you, but he never held a grudge or anything, you know.

You just had to take him. He was nice, I liked him,

you knew where you stood with him.

But it was some of the men, one of the

guys -- when I see that with her with her cigarette,

when he reached in her pocket, that's what this one guy

would do to me all the time, and one time him and I

went down on one of the blast furnaces that was shut

down. I didn't know, you know, I just went in there.

I knew that in the winter we did maintenance on

different things, but I didn't know, and we went on

this blast furnace and it was shut down, and he bends

down, Bill, and his whole privates, everything is

hanging out. It's the God's truth, and all we were

doing was changing the filter. I mean I didn't even

see him. Put the things on, he got up and went on out

to the truck. I would tell my friend, who was Bob

Arrowwood, his wife worked there in the machine shop,

and she cried all the time, you know, the way they did

to her over there, but I could handle that.

Then when they got the boss, and I wouldn't

want to mention his name, but when we got this one

particular boss, he made me -- it was a living hell for

me. I mean absolutely -- he would make me wash the

trucks, and it wasn't like I didn't mind washing the

trucks, but he would stand out there and watch me, and

it was just awful with him.

And when I went into the last job I had, I

had a general foreman named Norman Miller, and right

before I retired, right before I went out sick,

Norman

Miller told me that when I first came over -- I could

tell when I came there how the foremen were watching

me, you know, and stuff, and he told me that this

foreman told him that I wasn't any good, I wouldn't

work, I was nothing but to stir up trouble, and

everything, and he told me, he says, "You know, Mary, I

have never found you to be that way," but that's what

this foreman, you know, and I don't know what else.

I would have to speak good of everything I

did down there except in the crafts, and it's just like

that movie, and I mean the girls up in the locker

rooms, they knew it.

MR. BARRY:

Did you talk about it in the

locker rooms?

MS. LORENZO:

Oh, yeah, everybody knew,

everybody knew the shit they put me through in

refrigeration.

Oh, you want to hear about the telephone

call. That was in I think '82. I got sent to Pennwood

Power, and like I said I went in the electrical

department, I was scared to death of electricity.

Well, I couldn't get any worse than down there in the

powerhouse, but I was working in the powerhouse, and

this one guy from ERS, they had sent him, too, the

lineman, and he told them he couldn't climb and he was

going to bump me because he had more seniority, and I

remember the general foreman called me upstairs, and he

was on the phone and he says, "What is he going to do,

what is he going to come over here and tell us he can't

do," and he had told me, he said, "Mary, you know, do

everything you can." So when I went out there, Steve

Stahoviak -- have you ever heard him? He said, "Girl,

get them hooks on because you are going to climb a

pole." I said, "Oh, okay, I can climb a pole," and he

says, "Real high." I said, "Well, I'm not afraid of

heights." I climb on the cranes, you know. He says,

"Well, this is nothing like a crane." Well, Bill, I

always climbed trees. You know, I grew up in the

country before I moved to

Cockeysville

. That's why I

like that kind of work, and I climbed the pole.

They brought me out and had all the men come,

and I mean you are standing there, and it's not hard,

it's all -- because you've got to be bowlegged, have

your legs bowlegged get those spikes in. So they had

me do that the first day at the end of the day. I

would say it was about 2:00.

So the next day they sent me on a job and

they sent me with my foreman. I had a foreman

Mr. Cook, and they sent me over to I think it was third

strand or one of those strands over there now, I can't

remember, but he came down and he told me I had to go

with him, I had to go climb, so I didn't know. It was

him and another foreman and me, and they took me down,

way down to the coke oven. I was all by myself, us

three, and I didn't know to say hey, where is the union

rep or where is somebody else, I would go down there

with them, and after I got involved I knew it was their

word against mine, that's why they did that.

So they told me put the spikes on and climb

up the pole and keep climbing until they told me to

stop, and I couldn't have my belt, my belt was hanging

down, but you know how they have them hooked when they

are not around the pole, so I kept climbing, and I was

getting up really high, and I knew you didn't have to

touch that high voltage, just get so close, so I kept

climbing. I guess they were waiting for me to say I'm

scared or something, but they said okay, you can come

down.

Well, coming down, see that's where I didn't

shove that spike in far enough, and when I pulled the

other one out I cut out. Well, going up the pole you

use the spikes, but they did have those hand things to

hold on. So when I started to fall, my arms were going

boom, boom, boom, and I grabbed ahold, but the rawhide

on the spikes got caught around one of these hooks and

my foot is up in the air like this and I am hanging

like this and I couldn't get my foot undone, and I'm

looking and I'm really psyching myself up thinking now

I'm going to fall, how can I push myself so I fall on

my whole body instead of my head or my leg or

something. And finally I said to Mr. Cook, I said,

"Cookie, I can't get my foot undone." After it all

happened I wouldn't have fallen because I would have

dangled by my one leg there. He says, "Wait a minute,"

he came up and he said, "Can you give me your belt,"

and like here I am hanging, my foot up in the air. So

I lean my chest up against there, and I had my arm

around and I unhooked it and then I grabbed -- I

brought it around. Of course I had to hold on to here

real quick, and he wouldn't hook it for me, I had to

hook it myself, and then when I sat on my behind on my

belt I got my hook undone, and I went on down the pole.

So he says to me, "Do you want to go to the

dispensary," and I said, "No." I said, "I know I

bruised the hell out of myself," but I said, "I know

nothing is broke," because it was just burning, and he

said, "Okay."

So they took me back to this job, so I don't

know what the position was, but what we were doing --

they were running new cable, and that stuff is about

that thick, and they had put me on the job where they

had the truck and they reeled it.

Now I had to pull this cable and keep

throwing it, but I had to make sure that I stayed away

from him because this reel was going around, but it

wasn't like you just hold it here, you had to keep it

going, and I thought my chest was going to bust. I

mean it was really -- where is the end of this cable.

So I did that, and the end of the day we go

over to electrical construction, and of course the men

all had bathrooms, and of course I didn't, but I didn't

want to make a big stink, I just wore my clothes home.

So I forget what his name, Richard something, he came

and he says to me, "You are laid off," this was on a

Tuesday. I said, "I'm laid off? Why am I laid off?"

He said, "You can't do the job," and I said to my

foreman, I said, "Cookie, what did you ask me to do

that I couldn't do?" And he said, "Mary, it's not me,

it's higher up." So I just started crying because I

couldn't afford it with the kids. I'm hysterical

crying, and to this day I don't know who it was,

somebody came and said get to the dispensary.

So I went flying over to dispensary, and I am

just sobbing like a nut, and I see Bill Nugent, and I

think it might have been -- I don't know if it was

Eddie Bartee or there was another black gentleman I

think that was in the union at that time. I know Bill

Nugent.

But anyway, I stopped my car in the middle of

the road when I see them, and I'm flagging them down, I

mean I am crying my eyeballs out. Bill goes, "What's

wrong," and I told him that they laid me off. He said,

"Well, they can't lay you off because you hurt

yourself." I said, "They didn't lay me off because I

hurt myself. They said they laid me off because I

couldn't do the job."

So I go in the dispensary. Well, they put me

on SIP, so that saved me until a couple of days, I

don't know. I would have been laid off Friday. They

had another layoff, they knew it, it was just they were

going to show me they were going to lay me off. So

Bill Nugent told me to go to Bernie Parrish, and I went

and --

MR. BARRY:

And Bernie Parrish was?

MS. LORENZO:

The chairman of the civil

rights. He was the staff of civil rights. They said

“You know, she's a nut,” but I went down to the EEOC, and

they said to me you need to go to the NLRB, I don't think

your union is helping you, and I said, "Oh, I couldn't go

against the union."

MR. BARRY:

And it's funny, because Bernie

Parrish's dad was real active in the steelworkers civil

rights suit.

MS. LORENZO:

Well see, that's where, Bill,

and I noticed this when I was the chairman of the civil

rights, some of the things with the girls, they went

into expediting positions. Now I know that the

expediter in our shop was a male, and he had unlimited

overtime. Now when these girls had it, it happened to

be a white girl, and I went to Everett Hawkins, he was

for 9116 then, of course I forget all, but I said,

"

Everett

, they are discriminating against her, all the

men." He says, "Don't start that word, I don't want to

hear that word," and this is what made me angry because

I remember a black girl calling up about changing her

schedule or vacation or something, and the foreman

says, "Oh, I don't have time to talk about this shit."

Well, they wanted to file this big suit, and it made me

mad because you don't want to be divided, but they

couldn't see what they were doing, you know. I mean we

were in the same place they were, and I mean when I got

in the mill, most of the times the black men were the

nicest because they knew what you were going through,

but the union, when you got to the union, you didn't

find that.

And people knew about it, but I went downtown because I

didn't know all the procedures and everything, and I went

downtown, but I wrote letters to Lynn Williams [President of

The Steelworkers International].

MR. BARRY:

And downtown is what?

MS. LORENZO:

EEOC.

MR. BARRY:

Let's go through what happened

with Bernie Parrish.

MS. LORENZO:

I wrote letters I think to

Mr. Parrish. I think I just threw them away, I will

look and see if I can find them there, but I wrote to

him, and I went up to Dave Wilson and I told Dave.

MR. BARRY:

And Dave Wilson was?

MS. LORENZO:

Dave Wilson was our [District]

director at the time.

MR. BARRY:

Did you go to any of the local

officers first?

MS. LORENZO:

I belonged to 2610 at that

time, and it was Walter Scott, and I'm trying to think

who was -- GI Johnson was our civil rights man. He

knew about it. I mean people knew about it because it

was like talked about, and I can't remember all the

procedures, but after I got involved in the union, I

realized what I done wrong. I didn't go and -- I

didn't make that shop steward file a grievance and

stuff. I went downtown, and at that time -- it wasn't

on

Center Place

, it was somewhere else, right off of

Franklin I think it was, and I went down there and I

talked to an investigator, I think it was a Mr. Blue I

talked to an intake worker and it was turned over to a

Mr. Blue. And so they came and they investigated, and

the Bethlehem Steel said that everybody coming in that

department that they started at a certain date, they

named a certain date, that everyone coming in there was

required to climb, because a lineman is an

apprenticeship program, you don't just go in there and

become a lineman. So I thought well, okay, if they

didn't ask me to do anything more than anybody else.

So I was talking to Bob Arrowwood, and he was

in my department then. Of course I was laid off, they

were working, and he said, "Me and Melvin were over

there after that and we were there for six months." He

said, "We never climbed." He said, "In fact, they kept

saying to Melvin hey, if you don't shape up, we are

going to make you put them hooks on."

So I called back downtown to these people and

I told them, and they talked to Melvin and I think Bob

and Joe Reichenbach, and they found out that the story

was different. So anyway, EEOC ruled in my favor. Of

course Bethlehem Steel filed an appeal.

MR. BARRY:

And how long did this take?

MS. LORENZO:

Oh, it took years.

MR. BARRY:

And were you laid off while this

was going on or on SIP?

MS. LORENZO:

I was laid off, I can't

remember when, because see, Bill, I would bump in, I

would bump back in, I would go anywhere, because that's

where I went to work over at the BOF and stuff. I

would bump in because I needed my benefits and stuff

for the kids, so I don't really know.

I didn't stay out there until they called me.

I would come back in. But anyway, Bethlehem Steel was

found guilty, and of course they filed their appeal.

Now, I never went to any other hearing, and

then it came back that they were not guilty, that there

was another woman that was in that department who

climbed the pole and I could not climb the pole, and

that was not true and Bernie Parrish knew that wasn't.

She was a black lady, and he knew that was not true.

It was two girls were hired off the street

for the apprenticeship program. One was a wireman and

one was a lineman at the time, and for some reason -- I

don't know if they stayed with the company, but I do

know that the black girl could not climb the pole,

because the guys told me that she didn't, and when I

went up to the union, I went up to Walter Scott and

them and said well, tell me what is this name, who is

this girl. Nobody -- but you know what I found out

later? Bernie Parrish filed a discrimination lawsuit

for that girl in the line gang.

This is like I said about this separate,

which I thing has hurt -- started hurting the union,

because I think like I said when I went in there, when

I would get into areas that the women weren't in, the

black men were the ones that helped you the most

because they knew what it was like, but it was our

union, and like other black people aren't going to go

against GI Johnson or Bernie Parrish or anything and

say hey, what do you mean, you know, and I found out a

lot of times, Bill, for the average person like me, you

don't know and they don't give you help, and that's

where I fought the union, because I figured I pay my

dues for you to help me. You are kind of like a lawyer

to me, and I remember -- I will show you one thing.

When I went to the civil rights the first

time, there was this guy that got hurt on the job, and

he had taken -- he was a maintenance tech and he had

taken every test. He worked over -- he was in mobile

equipment maintenance, and he had gotten hurt, a tire

blew up on him and it fractured his leg and his leg was

stiff, he couldn't straighten his one leg, and he could

do everything else with some reasonable accommodations.

He would have to have maybe a little crane or somebody

to come over just give him a hand to put stuff on the

table. They wouldn't give him his job back, they

wouldn't give him a disability.

Now of course his lawyer got him a

disability, but he wanted to work because he needed the

benefits. He was only I think 47 years old, but he had

20 years I think, 27 years, and he went to people and

nobody would do anything, and he came to me, and this

was -- I had just came back from a conference on

Americans with Disabilities, and so I called their

Washington

hotline and told them. I said this guy --

he has tested. Normally they will say oh, she was

grandfathered in or he was grandfathered in, he can't

do it. This guy tested and passed anything, and he was

willing to take anything for them to let him back, and

they wouldn't let him back to work.

So I even went to an attorney downstairs [to the

office of Peter G. Angelos, who rented the second floor

of the Local 2610 hall for many years] and

talked to the attorney down there. Do you know what he

told me? “Are you trying to get yourself fired? You

are going to get yourself in trouble.” I said, "For

what?" “Because that guy's attorney told him I can't

get your job back, they won't give you disability, it's

up to your union.”

So when I called this Americans with

Disabilities, the guy told me get a pencil and piece of

paper. He said you have to write this exact wording

that I am telling you, and I wrote the letter exactly

like he told me, and we sent it in, and they gave him a

disability pension with Bethlehem Steel. So he got

his, and he came and he had -- his girlfriend had a

surprise retirement party for him, and she called me.

She didn't know me or anything, and she asked me if I

would come. She said nobody is going to tell him that

you are coming she said, and so I came over, and his

mother and father, one of them was in a wheelchair and

they cried when they seen me for helping him, and he

was so happy, and I went -- after I retired I joined

the Silhouettes, and the lady working there, you know

you start talking, her husband worked at

Bethlehem

Steel and we were talking, and she knew this guy, and

she said oh, we're in the same club and she told him,

and he sent me a dozen red roses, but here's what he

gave me, these balls. [displays a package of two brass

balls} He's the only one at

Bethlehem

Steel, that's what he gave me for helping him. I

couldn't get over it, and that attorney down -- Peter

Angelos, Richard Dickson, whatever his name is, I went

to him, Bill, about my hands, about my shoulders, and

he would tell me nothing, and this guy that worked at

my department doing the same job as I did, he went over

there and he told him oh, yeah, that's job related and

they filed for -- Pete got job related on carpal tunnel

and stuff on his hands, he is telling me that, and I

went to him the last time before I retired. I went to

him because I can't remember what was going on. Maybe

it was when I had my thumb operated on, and he is

sitting there and I said, "I don't know why I am

telling you this," and he says, "Why do you say that?"

I said, "Because you look like you could just puke." I

mean that's what he did. I mean he was looking at me

like disgust, and I told him, I said, "You look like

you could just puke." I hate to use those words, so I

got up and I left, and when I had -- I was off, had to

have my shoulders operated on and my hand, and Social

Security gave me a disability. I mean I only filed it

because I had to. I was out over a year.

MR. BARRY:

How did you hurt your shoulders

and your hand?

MS. LORENZO:

I think from like in

refrigeration I would have to carry the freon bottles

and everything, and they weighed 30 pounds. I would

put them up on my shoulders because it was easier to go

up the steps. We have to climb up the steps in the

cranes and everything, and then when I got into this

new job, which was the best job I loved since I have

been down there, but it was hard, everything --

MR. BARRY:

What was the job?

MS. LORENZO:

That was -- where the heck was

I? Motor repair. What was I? Isn't that awful? But

I built the wheel assemblies and stuff for the overhead

cranes and the magnets and everything for that, put in

new bearings and stuff, but everything was so heavy

that a lot of times we only had the one crane, and if

the crane was not -- you know, being held up, I would

just take my shoulders like and push stuff over, and I

had this shoulder operated on twice and this one done

twice, and I had like some kind of little round thing

put in my thumb, and my shoulders still bother me, and

I haven't worked since 2001, but if Social Security

hadn't gave me a disability, I probably would still be

down there with my SIP every year or something with

this shoulder, but I would have still been working

because I would have like to have that 50 grand. Now I

don't know what else to go on to say.

MR. BARRY:

Well, how did you deal as a

single parent with shift work?

MS. LORENZO:

Well, when I first started when

I had shift work I was married and then --

MR. BARRY:

And you were living here in

Essex

?

MS. LORENZO:

Yeah, I lived across from

Salvos, and then we bought this house when this

development was first built in '71. Moved in here in

February '71, and I started at Bethlehem Steel in April

of '71.

But my kids when my husband and I broke up, I

had six children, I had three by my first marriage,

three by my second marriage, and when we broke up, my

first husband, he could have cared less, he has never

ever seen his kids or could care less, and my

husband -- we always told him he could, but my second

husband loved his children, and I knew I couldn't take

care of six kids. I mean I knew I couldn't, so we

agreed that he would take those three, I would keep

these, and then in the summer when I had my vacation

the children would come up with me for those two weeks,

so that went on like that.

But right after him and I broke up, my older

boys were getting ready in the teenage years, and he

was very strict on them, and of course I would come

home and I would go to bed. I mean they would be

sitting here, everything would be fine, and I would

wake up three o'clock in the morning with the police

banging on the door because everybody would be coming

in to my house because I was asleep and all or I was

working, and it was -- I could never go through it

again.

I mean it was very, very hard times. I mean

I just said the police were out at somebody else's

house a couple of weeks ago, and I was out on the porch

and I said to the next door neighbor, I said, "Whew, I

can remember the years when they were always here." I

said whenever you seen the police, it was here, and

then my son, my oldest son committed suicide.

I got laid off in September of '82, and he

committed suicide in December 10th of '82, and he

had -- his girlfriend was pregnant and my granddaughter

was born six months after my son died to the very day,

and she just passed away October 23rd. She had

cerebral palsy, and she had gotten a cold, and her

mother, her mother was so good -- really took good care

of her, and she would stay in the room with her when

she would get sick, and Mary woke up, she was gasping

for breath. She called the paramedics, and they lost

her twice before they got her to the hospital, and then

at the hospital and she had been with -- she wasn't

brain dead because they took her off the respirator,

she could breathe, but she had so much brain damage

that she would never wake up or have -- she would have

to be tube fed and all.

So her poor mother, they told her you know

why we are telling you this, and she said yes. Oh,

God, Bill, it was awful because she crawled in that

bed, she loved that little girl, and I guess it was

maybe two hours after that the doctor came in, he said,

"I think the Lord is making the decision for you,"

because her organs started shutting down, and he told

Mary, he said, "By law we have to go there and give her

needles" and stuff like that to resuscitate her and

Mary said no, she said she just didn't want to be in

there, and they said well, it will take a couple of

hours. So that's what happened, she passed away

October 23rd. But I mean it was like -- now I know why

God has you have children when you are young, because

if I had them now when you get older, things -- you

look at things different.

I mean now do you think I would put up with

that shit at Bethlehem Steel? No way. But at that

time it's like oh, my God, I've got to go to work, I've

got to do this, and I mean when my husband left here he

took everything, he took everything. We had a very,

very violent relationship, and that's why I got out

because it was getting really -- and the only thing --

I mean I could take pretty much take care of myself,

but I would still get the shit beat out of me, you

know, so when we decided to break up, I said look -- I

was afraid to come around him. I said when you move

out, I will come back in, and I had my neighbor, I said

let me know when I can come in, and she said the moving

people were out and the guy, one of the moving men --

because she asked if they wanted some iced tea, it was

in the summer, and he said what that man is doing to

that house is a shame.

So when I called her, she called me when they

were gone and I said, "Well, I will have to come back

and clean it." She said, "Well, Mary, I'm going to

tell you it's not going to be hard because he took

everything." Bill, he took switches off the light

switch to be nasty, took my stove, my refrigerator, and

I said well, what's the sense, I couldn't get upset or

anything because there wasn't anything I could do, but

I went to take a bath and there wasn't any hot water,

and I said if I go downstairs and he took the furnace,

I'm really going to be pissed. What it was, when they

took the stove, they had to cut the gas off, so I

didn't have hot water for the heater, but I made it.

Like I was just talking to my daughter

yesterday, because she's living in

Las Vegas

, and I

always wanted her -- I didn't try to get her down to

the Point because I know how dangerous it was down

there, and especially think now with more young girls

because they are really -- I knew some of these young

girls would come in that they just hired and they would

have them feeding out there on those lines, and Bill,

when I got there, those men had to have fifteen years

or something to get on those lines.

I mean I can remember a girl coming in there

crying because she was scared to death. She wanted to

work, she was willing to do anything, but she didn't

like that because it scared her to death, and I didn't

push my daughter, but I was telling her come on, Stace,

you know she was driving a limo, she was driving a cab.

I said everybody has got to work. I said you are going

to find very, very few people that like what they do.

I said I knew I had to work and I was going to work

where the money was, and I said, "And look, I've got a

good pension, I have good Social Security, I can do

what I want." I would like more, I lost 300 when they

did that and the benefits, but I said some women I know

live on $800 a month, and that's what I tell my

daughter-in-laws and all them.

Bill, I can remember when I would be working,

because I was young like everybody else and we would

stop on

North Point Road

, and sometimes we would go --

instead of going home, we would go for breakfast and go

to work. Now that would kill you, but I can remember

some of my friends would be laughing because they

didn't work, they would laugh at me ha-ha, you've got

to go to work, but whose got the last laugh now? And

when you are old, I don't know what I would do at this

age not being able to have anything that I enjoy.

MR. BARRY:

Let's go back to how you got

involved in the union.

MS. LORENZO:

Well, I got involved in the

union through Sandy Wright, because when things would

happen to me over in refrigeration, and this is like

where --

Sandy

is a very, very smart girl --

MR. BARRY:

And what year would this be?

MS. LORENZO:

I think it was in '91 or '93.

It was when I went over --

MR. BARRY:

So you had been there almost 20

years?

MS. LORENZO:

I had been there, yeah, 20

years.

MR. BARRY:

You started in '71.

MS. LORENZO:

I started in '71 years, yeah,

so I had been there about 20 years.

When I would go through these things, guys

would take me, "Mary, do you know Sandy Wright? Go

talk to Sandy Wright." Well, it was again that I'm

going to take care of myself, you know, and I could be

used as long as they are not the only one being treated

bad, but anyway, Dave Wilson was married to

Sandy

's

cousin.

MR. BARRY:

Dee

?

MS. LORENZO:

No, not Dee. The one -- the

big lady.

MR. BARRY:

I don't think I know her.

MS. LORENZO:

You knew who he was married to

a long time.

MR. BARRY:

That was before I was here.

MS. LORENZO:

She was very involved in the

union.

MR. BARRY:

When I met him he was married to

Dee

.

MS. LORENZO:

Well, see, I started working

with

Dee

, and that's why Dee and I got along really

good because Dee and I, we worked over in the tin mill,

and

Dee

knew I worked, worked hard and she worked -- we

worked on pulling scrap and all that, but Marie Wilson,

that's who Dave was married to, Marianne Wilson, but

anyway I went up to the union -- no, Jimmy Harmon came

back and gave me -- it was at a conference in

Atlantic

City, a civil rights conference, and he gave me the

little brochures and all that, and it had about the

last women of steel.

So Sandy and I decided we would go up and

talk to Dave. So he said “yeah,” we wanted to go, so it

was me and

Sandy

and it was a black lady, I can't

remember her name, she lived on Elwood, she worked at

one of the other places that shut down, and a lady from

2609. We went up to

Boston

,

Cape Cod

or somewhere up

that way, and that was the first that I had ever -- I

had never heard of CLUW [The Coalition of Labor Union

Women], never ever heard of CLUW, and

I thought the CLUW was more -- I liked it better for

the women.

MR. BARRY:

Up until '91, were there any

women who were really officers of the union or active?

MS. LORENZO:

In 2610, no. Like I said 2609

is a whole different ball game, whole different ball

game than 2610. No, not that I know of. I think maybe

Sue Guido, but I never even knew she was any of this

until when I went over there, there were papers laying

around. The civil rights committee used to be about

fifteen people, and that's where I seen her, but so far

as ever any other woman, no.

MR. BARRY:

So what happened at the

conference?

MS. LORENZO:

So Dave Wilson gave me the

opportunity to go, and I went to that conference there

in

Boston

I think it was,

Massachusetts

somewhere, and

then we went to a convention in

Las Vegas

, and I think

that was in '93, and I was elected as a delegate for

the steelworkers from the District 8, because I think

it was like three of us, three delegates, and I mean

they had the vice-president -- yeah, I don't know, I

was elected delegate. So every time anything involved

in CLUW I was to go, and I was chairman of their women

and nontraditional jobs committee, and we put on a lot

of things, and one of our conventions out -- the last

one I went to in

Las Vegas

we had -- remember What's My

Line? It was me and it was two other girls, and we

were dressed like card hats and stuff like that.

Instead of having the audience ask me, because it would

be too -- it was too hard, we had about five people

behind us and the job description was -- I think it was

my job -- no, it wasn't my job, it was another girl's

job, I can't remember.

But anyway, they were asking us -- no, it was

my job and they were asking questions and then they

voted, and I don't think anybody got it right, because

then we had to stand up and say it, and the one girl

was a baggage handler and the other girl was a

communication worker I think it was, but we were

describing the job, what you would do on my job, and

once we went to

Philadelphia

we had a workshop where we

had Karen -- I forget Karen's last name. She was an

electrician, and we made little switches and stuff like

that, and they told women how to make the telephones,

move their jacks and things like that, and it was nice.

MR. BARRY:

Did you find women from other

industries were having the same problems you had?

MS. LORENZO:

Yes, very much, and especially

some of the new trades where the women started getting

into, some of the building trades, and a lot of it was

the same stuff. You know people feel sorry for you and

all, but people don't like to stand up. There's very

few that want to -- they see what you are going through

and they don't want to put themselves through it, and I

never blamed anybody for that because I knew it, I

knew.

When I was in refrigeration, Bill, almost

every damn day I would either cry at work or cry coming

home, and I would say to Bob Arrowwood I shouldn't have

to do this, and I would go to my superintendent, and I

remember one time with the shop steward, I went over

there and I laid my head down, and I don't cuss, but I

came out with some very, very foul language, laid my

head, I was just sobbing. I said you have got to do

something with that blankety blankety foreman. I mean

they knew what he was doing to me, and the shop steward

was there, and I remember the one that -- you know how

you keep getting elected and elected, and the only time

you see them is election time. He was very well aware,

and one of the new shop stewards one time--the older one

was on vacation and this guy from electrical

construction came, and I forget what the problem was at

that time, but when he went in there the foreman starts

talking awful about me to him, and he said, "Wait a

minute, wait a minute, I'm her union rep, do you

realize what you are saying to me?" But he had gotten

away with it.

MR. BARRY:

Who was that new steward, do you

remember who it was?

MS. LORENZO:

That was Larry Burke. He

only -- I only think he ran that one time because

nobody did anything, Bill. It's unfortunate to say,

but they didn't. It was like if I tell you what your

rights are, I've got to work and do my job, and that's

sad, it's really sad.

MR. BARRY:

Did you ever have meetings with

other women at the plant to try and --

MS. LORENZO:

I tried to get women involved

in the women at steel. I don't know if I turn people

off, I really don't, because I would take stuff all

around. I just don't know why I couldn't get the women

involved.

MR. BARRY:

Do you think it was because they

were just scared?

MS. LORENZO:

I don't know. I got Flo. I'm

the one who got Flo, and I took -- I see Gail Fleming,

she was in the paper where she is going to CLUW and

stuff now. I got Gail and all. Now Flo did things.

Gail was pretty much ready to get out of work, but I mean --

and then see, too, Bill, a lot of times women -- I

could do what I did in the later years because I didn't

have a husband. A lot of husbands aren't -- they just

aren't understanding, and now I'm sure it's got to be

harder because how can you buy a house? I know my son

and his wife, they are both working, and I mean he's

got enough problems. I'm sure if she came home crying

all the time he would be quit the damn job and go

somewhere else, so that creates a problem.

I just wish that there would be something

that if somebody had a problem like that, people that

knew what it was like could go to somebody -- I don't

know if it would be like an attorney or if it would be

an arbitrator or what, who -- I mean I don't know how

to explain it, help them, because you shouldn't have to

work like that.

Luckily we didn't have outhouses emptied on

us and stuff like that, but I mean when the girls went

to the coke ovens, I mean there were many a girl, Bill

could tell you, they come around the corner and the guy

was going to the bathroom, because a lot of times they

really forgot, too, that the women worked there.

I remember one in the coal fields, a lot of

the girls worked in the coal fields, and I remember

this one girl, she was so funny, and our bathroom in

the coke oven had been a men's bathroom, so when we

came there they had it divided in half. Well, OSHA

came down because it only had two doors. Now it was

just one and one, so they had to make a door in the

back, and it was months and months, you know, we had

the holes knocked out, you had the tarp laying down. I

remember this girl Libby, she went -- everybody would

take their clothes in the shower with them because they

had the one big shower, and Libby says I'm not taking

my clothes in there any more. She said if they haven't

seen a woman by now, tough shit, but it was so funny

because when we first moved in, they didn't brick all

the way to the top, and we caught where the guys were

looking in there. It was hysterical because it was

like school kids, and then we had windows and there was

no air conditioner or anything, so in the summer we

would open the windows and we were across from Kohl

Chemical, and that was a couple stories high, and after

awhile some of us happened to notice there's all these

men standing on the railing, they could look right into

the bathrooms, so it was funny. And this girl Libby

after we discovered that, they had a men's bathroom

down in the coal field, so that the girls went over on

this belt line and they were standing up there. Well,

you should have heard the stink when those men because

the women when they caught -- then the woman started

ha-ha and it was hysterical because when it was us, it

was like oh, God, guys will be guys, but with them it

was a whole different story. It was funny, and I

worked on the belt lines like how that girl did in

there.

MR. BARRY:

You've been talking about the

movie, this is North Country, and what was your -- what

got you to see it?

MS. LORENZO:

Because one of the girls on my

committee was a miner, her name was Bonnie something,

but she was from I think

Pennsylvania

, the mines there,

and I think she got involved in the union kind of to

get out of that, because she would tell us some of the

stories that happened in the bathrooms and stuff, and

she didn't really -- she didn't come to that many

meetings after I became involved, because a lot of

places were small and it cost -- when they have these

conventions, except for Vegas, these hotels are

outrageous, the prices and all, but I knew -- I mean if

they had the women in the building trades, you are

going to find the same thing.

But now they have a young girl that was in

electrical construction. Now I talked to her -- I

don't think -- if she had any trouble with any of the

men, she never said anything, and I asked her, and it

was because they hired a girl in electrical

construction, they hired an ironworker and they hired a

maintenance tech, and the ironworker, she could pretty

much I think take care of herself, because I had said

something to the little girl, the electrician, and she

had met her like when they went on the stadiums or

different jobs for the locals before they got hired

there. She said oh, Priscilla can take care of

herself, but Priscilla ended up I think drinking or

doing drugs or something and not showing up and she

ended up losing her job, but Sandy -- the guys, I never

heard any of the guys say anything bad about her. They

said that she was really a good worker, and she could

worker harder than some of the men. She was a very

tiny small girl, but she never ever said she had any

problems, and it didn't seem like over there -- but see

with her it was at this time she was about the same age

as the new men coming in, and they all were learning

and she knew what she was doing, so I think it was a

little different than us women being -- I was like 31

when I started being thrown in there with people that

didn't want you there and weren't going to show you,

because that's how the black men, they wouldn't show

them anything, and so I think it's a little different,

because the other girl, the maintenance tech I think

she could pretty much take care of herself, and she

never really complained about it either.

MR. BARRY:

So you saw the movie. What did

the movie bring back for you?

MS. LORENZO:

Oh, I'm so glad you didn't come

that day, Bill. I called my brother, I said Bill Barry

from the college is going to come talk to me about me

working at Bethlehem Steel. I said I just finished

watching that

North Country

. I said boy, am I glad he

is not here, because it sure has got me pissed off. I

said it brought back memories, and I mean I always cry

some of the stuff because I can remember one time,

Bill, and my problem was my father and my mother, they

didn't have much of an education. My father was a

truck driver. They had seven kids, and my father

always taught us and all my kids were was whatever you

do, go out and work, don't ask nobody for nothing,

don't take nothing from anybody you don't know, so that

is how I always wanted to work, and I always -- if I

couldn't do the heaviest kind of stuff, I tried to say

well, I will pick up this for you and even it out, and

it was just so hard for me to see that this didn't make

a shit, they did not care and I'm talking about

superintendents.

I went over about this Mr. Hooth, and the

superintendent I had now was gone, and I mean I was

crying so bad that you know you are trying -- and snot

flew out of my nose, that's how upset I was. You know

what he said to me? "Get out of here, get out of here

and get control of yourself." And I mean it was

like -- you know what I mean? It was just awful,

awful.

And like I said would it be different now?

But you see that's how supervision felt for us then. I

mean not all of them did, but now it's like that's how

all companies are feeling about their people. You

don't care.

My son was a supervisor, operation

superintendent over at Medical Waste over on the other

side of the Key bridge, and this one guy was really

having financial problems, and he came to my son, and

of course my son was in the maintenance -- that's what

it was, maintenance guy, and he went to the big boss

who would have had to okay it. The guy wanted his

vacation, his money and not take the vacation, and

Michael said here this guy said -- it wasn't that he

was asking for a loan. He said, "Mom, he couldn't have

cared less, he didn't care about what that guy wanted

or anything," no. Then everybody would want to do it,

but see my son, he couldn't -- he drives a truck

because he couldn't be -- my son got in trouble and he

was in prison and he was sentenced to seven years, but

he served like three years, and he was married and he

bought a house in

Dundalk

, and what it was he was stone

drunk. I had been down his house that morning, I was

going to a union meeting, and he worked up in

Cockeysville

for Maryland Specialty Wire, and he was on

the 11:00 to 7:00 shift and he had just gotten home,

and I came over there and I said, "Come on, Mike, let's

go out and get something to eat for breakfast. I want

to go to the union meeting later," and he said, "Oh,

mom, I'm so tired," because he had worked the 3:00 to

7:00 and the 11:00 to 7:00, and so I said okay.

So I'm getting ready to go, and I'm not one

of these mothers that it's this guy's fault, but this

guy was -- he is from the neighborhood, and whenever

the shit would always go downhill, he was always in the

middle of, but he never got in any trouble, but he was

always the one like this. So he came over and he said

to Mike, "Come on, let's go out and drink." So they go

out and they drink, they got plastered and they got in

a fight with two guys, and my son goes away to jail

because he had been in trouble as a juvenile.

So anyway in order to come out, they try to

see if he got a job program and all, and this Dave

Fenwick, who was in refrigeration, the only guy that

stood up for me, he's dead now, he said to me, "Mary,

I've got a friend that works at the one Medical Waste

that was a steelworker. He said he would hire Mike."

So Mike got out and he went over there and went to

work.

Well, he was such a good worker. He belonged

to -- it was BFI and they had what they call a

chairman's club, and the first year he worked there,

Bill, he was named to the chairman's club, and this is

something that -- here's what it is. Only five people

or something out of this company. But anyway, he got

all these pictures. This is how many people were up

and only five were chosen and he was chosen the first

year.

MR. BARRY:

Good for him.

MS. LORENZO:

But he couldn't do it, because

he was brought up by work, and he was a supervisor and

he would tell the guys to do something and they would

say they didn't know, and instead of Michael saying

okay, here, give me the wrench -- he would go to the

job, and after awhile they seen that, and then the

company, too, when these -- whatever they -- the

incinerators would have to be relined, he would have to

stay there around the clock because you would have to

turn up so many degrees, and it just got -- he couldn't

take it because then they started hiring people that

didn't want to work, would bring their kids there in

this medical waste place, said they couldn't get a

babysitter, and he just started drinking, so he said he

had to get away. So he got his own truck and he says

he is better like that, but he made good money, but he

just couldn't handle that. But that's the story of my

life, all these things.

MR. BARRY:

So you left Sparrows Point in

2001?

MS. LORENZO:

I went out, I had my shoulder

operated. I officially retired I think it was May of

2003.

MR. BARRY:

Right before the end?

MS. LORENZO:

Right before the end.

MR. BARRY:

And what was it like at the end

of

Bethlehem

Steel? How did you guys feel?

MS. LORENZO:

Well, see, I wasn't there, I

didn't even go back for my retirement or anything

because I had been off for two years with my shoulders.

I went to those meetings, and I mean I

retired -- well, when I got the disability at

Bethlehem

Steel, I had to pay them money back because they were

paying me sick money, so that's when I talked to Jim

Hubert, and he asked me how much time I had and he

didn't know, I don't think he knew all this was going

to come down then either, you know, and I had 31 and a

half years. So I thought I was getting $1,800 a month

pension and $1,500 in Social Security, boy, this is

great. So I thought well, yeah, they are paying my

medical, and that's how come I retired.

If I had known that the bucket was going to

fall out, I would have tried to go back to work and

work, and said God, please can't you say I tried again

or something.

I don't regret leaving because I lived for

that day. I hated getting up, and I wanted to work the

day light so I had to sacrifice getting up, but I

always said I don't care if I don't do anything, it's

better than being there, I don't care, because since I

have been out of there, Bill, I haven't had a cold, and

I was getting lung infections. The last year I was at

the hospital all the time because I couldn't breathe.

They would have to give me those treatments where I

would have to breathe that mist in and everything.

Since I have been out of there I haven't had that, but

I have lung problems from there, but I haven't had

colds and all like I was getting.

MR. BARRY:

So did you lose some of your

pension?

MS. LORENZO:

I lost 300 and some dollars a

month.

MR. BARRY:

Plus your insurance?

MS. LORENZO:

Plus my insurance. I had kept

my insurance, I was paying -- it went from $84 to $534

a month, so I paid that because I always had Blue Cross

and I always liked it and I wasn't 65 yet. So then

when we got the government help, I only had to pay

$187. So because I went out on disability, my

disability -- I got Medicare earlier than I would have.

I think I got it when I was 64, because I think you

have to be out two years or something, so when I got

that, then I lost the other, so my insurance went up to

$295 a month, which I still paid. And then come

December I got a letter that the insurance was going up

again, so I called and it went up to $428, and I said

well, enough is enough. So that's when I went and I

got the Medigap Blue Cross Blue Shield

Maryland

, it's

$143 a month I think it is.

MR. BARRY:

And the rest you are on Medicare?

MS. LORENZO:

Yes.

MR. BARRY:

You were talking about your kids.

One of the questions we always ask people is whether

they would have had their kids go to work down there.

MS. LORENZO:

It would depend on -- my

daughters, I would have to know where they were going

to go to work, because on the steel side -- my

daughters are frilly frilly, you know I don't think --

but she's got a mouth, but I don't -- she probably

could because she's strong, stronger than what she

appears to be, but it's dangerous.

My one son by my second husband, he was going

to go there, was going to work during the summer. He's

a design engineer for Nissan up in Detroit, and he was

going to work there during the summer, but he was still

in college and he was getting ready to graduate, and he

had a hernia so he couldn't. Had to get that operated

on while he was still under his dad's insurance, and

I'm kind of glad because he is such a smart boy. If

something would have happened to him, it would have

been terrible, but I was so glad. But Carolyn Holt --

do you remember Carolyn Holt?

MR. BARRY:

No. I remember the name.

MS. LORENZO:

She was president of Local 9116

at first. She was a pistol. She was really a good

union --

MR. BARRY:

She probably was the first woman

who was an officer?

MS. LORENZO:

Yes, she was.

MR. BARRY:

And what year was that?

MS. LORENZO:

I really don't know. It was

right after they won that lawsuit I think, and see --

MR. BARRY:

Just for the people that are

watching this, Local 9116 covered what jobs?

MS. LORENZO:

That covered your clerks and

your expediters, more or less the people that worked in

the office. I mean they were out in the mills, the

expediters and stuff, so it wasn't like in production.

MR. BARRY:

The local that Flo was in?

MS. LORENZO:

Yes. And they had won a

lawsuit, because they found out that the men and the

women were doing the same thing and they were paying

the men a lot more money for the same thing, and that

was in I think the '80s, you know, so that's what I'm

saying. When I seen this movie, it was like -- but

like I told you, I bet you could go to any

apprenticeship place or any job site that's got the

women and I'm sure they have stories, too.

MR. BARRY:

What do you think is going to

happen with the Sparrows Point plant?

MS. LORENZO:

Bill, I don't know. I know

that when I talked to the guys, they made more money

than they have ever made, and at first the profit

sharing and everything, they got the profit sharing

checks, and I do know that when -- I do think that a

big part of their problem was management. I mean they

had five bosses for four workers and then --

MR. BARRY:

And they were all relatives?

MS. LORENZO:

Yeah, and the stealing. I mean

come on. You've got to be a moron. See people would

report, nothing would be done, but that's the only

thing that makes me angry is that the salary people got

more benefits than we did and they are the reason that

the place has went under. I don't know. I don't like

all these foreign countries taking over our

manufacturing.

Like my son and I were talking or my

daughter, I said let me see if I know some unions out

there in Vegas, maybe you can get into something, and

she said, "Mom, out here in Vegas, believe me if you

want to work, you are going to work." She said that's

the place for the jobs, but the traffic is just -- it's

just boomed, and she said you don't want to work in

Vegas if you don't have a job she said because there

are jobs, but she said there's not manufacturing but

the housing industry and all that.

But one thing I seen out there -- now they

have to go get health certificates, they have to

apply -- they have to go through all kinds of stuff to

get a job as a waitress, and when I was out at my

friend Mike's house last year, I was flipping through

the TV and the local channel, it had people who were

denied this -- whatever this permit is to work. You

have to be checked for hepatitis. I imagine that's

probably just in the --

MR. BARRY:

Food handler.

MS. LORENZO:

Food, but all of these things,

and my daughter told me now it's really bad because

they go back ten years on your employment, plus they

are checking all your credit. If you've got bad

credit, they are not hiring you, and I mean I look at

the kids nowadays and I don't -- half of them don't

know the stuff that I can just still remember from

school let alone what I forgot, and I can't understand

what's going on, where are they going to get these

jobs.

MR. BARRY:

Let's ask the big question. How

do you win at bingo?

MS. LORENZO:

I win big sometimes, most of

the time. I don't know. Playing 36 cards at a time.

MR. BARRY:

Is that what you do?

MS. LORENZO:

Yeah.

MR. BARRY:

I know when I had you in class we

always used to talk, you were a little football and

basketball and that kind of stuff, so you moved up to

bingo?

MS. LORENZO:

No, I always played bingo. I

played bingo -- well, my oldest son would be 46 this

year, and I started playing bingo before he was born,

and of course then I could only go once a week, and of

course when I worked I couldn't go except on the

weekends.

MR. BARRY:

And where would you go; up on

Boulevard?

MS. LORENZO:

I started like over in Towson

down in that area, and I would go wherever I was

living, but now I go down in

Dundalk

, but with Las

Vegas, see I always saved -- I would always have $200

every month taken out of my pay and put in my Christmas

club, and I still do that, and that's the only money

that I take when I go to gamble. I mean I would like

to take $5,000 or something. I mean I have it to take,

but no, I'm not going to.

That's my friend Mike, he moved to Vegas, he

will be 82 in August, and he came back, he's got a

sister here and she's got Alzheimer's, and when I went

out last October and came back in November, he came

back with me. He was going to stay between my house,

her house and his nieces and nephews, and by the end of

December I had to get on the Internet and get him a

ticket back. He went back January the 6th, said he

couldn't stand it, it's too boring, and I mean he's on

a fixed income, he doesn't have a lot of money, but he

goes twice a day.

He knows when they have -- sometimes they pay

triple pay and he goes on them, and then they have like

these hot balls. When the hot ball gets to 4 or

$5,000, you go there, and they cater to them, they

cater to the natives out there, and like he gets three

free nights at the hotel and a slot tournament free,

and he lives there, so he just goes on down, and I like

it out there.

I'm hoping, because I'm a person that I have

to have the air conditioner on because I really don't

know -- but I say what do I do? I go from my air-

conditioned house to my air-conditioned car to the

air-conditioned casino. I just decided that it's a big

move for me really because my family is here, I love my

doctor, and those are the things that really have me --

is this really what you want to do.

My son, you know I have one child here in

Maryland

, he lives in Conowingo, and he told me “Mom, if

that's what you want to do, you always like to go out

there, go.” And my other kids, they said “don't save no

house for us, go and enjoy yourself,” and I think if

I've got 20 years, hey, I'm really going to be lucky,

why not go where I enjoy myself.

MR. BARRY:

All right. Any other memories of

your years at the Point? If somebody said to you what

was it like?

MS. LORENZO:

I can't describe -- I mean it

was interesting. It had its good times, it had its sad

times, but overall I think other than that specific

area, I can't say -- and the girls, you know. It was

so much fun when they had all the women, when they had

the coke ovens, it was so much fun to see all the women

down there working in the coal field.

Those girls would come in from these coal

fields and they would be -- we all wore long underwear

and then you had your dungarees, and then you had those

uniforms on, but they had to do that because the cold

gusts and they would come in like that, and they would

have -- their backs would be soot and they would have

to wash each other's back and stuff because you

couldn't get all that soot, and I can remember when we

would walk out, they had the quencher, and when you

first went there, because I ruined some clothes until I

realized you walk out and the quencher, they would

quench that coat and make it cold with water, and it

would have these little black dots. Now if you didn't

touch them and they dried, they would blow off, but at

first you go like this, and it was all streaks and it

wouldn't come out.

And they used to have a restaurant down

there, and it was nice, it was nice. I mean I didn't

like swing shift, but when I went into the labor gang

and it wasn't the best of money, and then I went

into -- I was just sweeping in the machine shop I think

they call it, the coke ovens down there in the

maintenance shop and that was pretty nice. Most of the

time I was the only girl around.

So when I went to refrigeration, the guy at

the employment office said that was the best job but

the worst boss, he is deceased now. His name was Larry

Reece, and Bill, he would holler at you, but if anybody

else said anything about his workers, he would jump on

them like I don't know what. Always took up for his

workers, and we were working over one of the hot strip

mills, and the mechanic asked me to go back and get his

lunch because it was lunchtime, and he says pick me up

a Coke at Servomation, so I'm driving the truck, I'm

coming down to go back to the job, and the boss pulls

up, I'm stopped, and he says, "Where have you been?" I

said, "I went up to Servomation, got a Coke." He said,

"If I ever catch your ass driving that truck anywhere

else" -- I mean I was like, and when I went back and

told the guy, he said, "Mary, he don't mean anything by

it." He said that's how he is, and like the next day

he says to me, "Hey, Mary, grab that truck and go up to

Servomation, and get me" -- he let me know, and that's

how he was.

But one time in the summer comfort cooling

always came last as far as refrigeration, and this one

mill, the office kept calling up, their air conditioner

was making noise, it was cold, but they said it kept

making noise and all. After about the fourth call, he

gets out, goes out, gets in his car, drives over there,

Bill, walks in the office, turns it off, said, "Ain't

making any noise now; is it? Out he goes, but he

passed away, but that's what everybody said, you didn't

dare say anything to him about his employees, but the

ones that took over after him they talk about their

employees like dogs, but he always took up for his men.

MR. BARRY:

Any other last memories?

MS. LORENZO:

No. The only thing, yes, that

I do regret is like I said most of the time I worked

down there I worked with all men, I was the only girl

and I had a lot of good friends, but when I retired,

that's the bad part about it is all my friends were

men. Their wives don't want you to come over, and a

lot of them even when you see them it's like hi, and of

course I know how, and that's the only bad thing

because I don't really have -- I never really formed

good relationships with women. I always did get along

better with men.

I did volunteer work for my doctor for

awhile, and her little receptionist was getting

married, and that's why she wanted me in there so I

could fill in for the two weeks where she was on her

honeymoon. Well, I know how she's young, she was

excited about her wedding and all, and I said to my mom

I'm not interested in that shit. I said they talk

about putting a coupling on that got stuck or something

like this, but I don't -- women can't understand, but I

just don't like to hear, but that's the only thing I

regret, because like I said I don't have -- like my

friend Mike, I met him at the bingo hall, and we

started traveling together because you had to pay

single supplement. He had asked me would I mind

sharing a room. I said I work with all guys, it didn't

bother me. I will flip you over across that room if

you bug me, but we have been friends, but we couldn't

live together. I wish we could, because he bought a

doublewide mobile that's bigger than this house, it's

longer, way longer than here, and it's too big. He

wanted to sell it to me, but he wants to sell it too

much, because he got all new carpet and all and all the

furniture, and I don't like his furniture. It's

beautiful, but it's not me with my dog.

But I said I wish him and I could live

together because it would be so much cheaper, but we

are like Felix and Alex, I walk in a room, and I don't

know what I do, I don't have to do nothing, Bill, but

I've got it torn up.

I had a friend who just passed away two years

ago, she was 49. She was over in the hospice, and I

was over there visiting her, and I'm sitting there and

after awhile I said, "Bec?" She said, "Yeah?" I said,

"What have I been doing?" She said, "What have you

been doing? Nothing." I said, "I know. Why do I have

this area tore up." I mean I did, I had Kleenexes here

and books. I mean I don't know why I'm like that, and

that's how -- when I go to his place, when I go to

Vegas, I will stay with him for awhile, but I always go

to the hotels two or three times. I can't stay the

whole month with him because I have to go in my room

and keep the door shut, I can't open the door, and I

make my bed as soon as I get up, but it's not to his

perfection.

MR. BARRY:

All right. Are you ever in

contact with Sandy Wright and some of the ones --

MS. LORENZO:

Sandy and I fell out. I don't

want this on there. The only one I usually keep in

touch with is Flo and Francis Almond. Another lady

Kitty, she retired before I did. Her husband worked

there, he retired so she had to retire, but no.

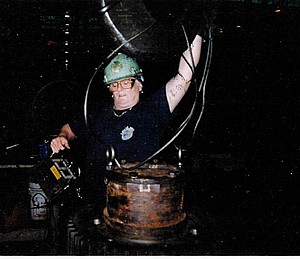

Photograph by Chiaki Kawajiri.

Photograph by Chiaki Kawajiri.